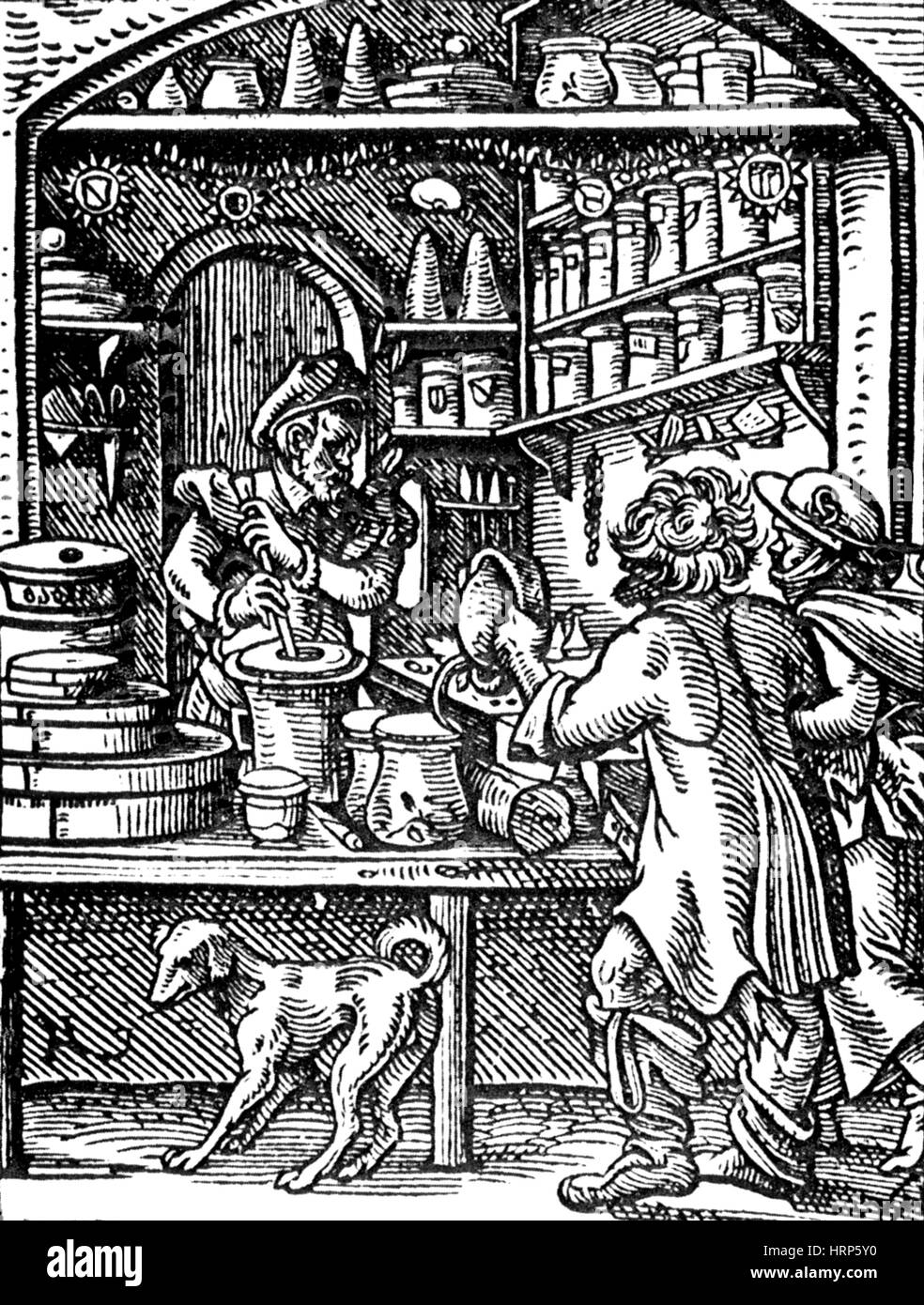

Apothecary - Medieval Jobs An apothecary dispensed remedies made from herbs, plants and roots. Medieval physicians were expensive and a priest often held this occupation, often the only recourse for sick, poor people. Artist - Medieval Jobs Artists were employed in the later medieval era by kings and nobles. Apothecary - Medieval Pharmacy Our medieval stillroom apothecary products are formulated from medieval and renaissance recipes with due regard to modern safety. Enjoy the luxury of traditional fragrances and botanical blends without the risk! Medieval doctors, at least in the later Middle Ages, learnt their expertise at a university and enjoyed a high status but their practical role in society was limited to diagnosis and prescription. A patient was actually treated by a surgeon and given medicine which was prepared by an apothecary, both of whom were regarded as tradesmen because.

- Medieval Apothecary Mask

- Medieval Apothecary Jars

- Medieval Apothecary Building

- Medieval Apothecary Names

- Medieval Apothecary Tools

- Medieval Apothecary Herbs

Stroll through the hipper districts of any American city in 2014 and you may experience the sense of time being slightly out of joint. On shop signs and menus, words that last flourished a couple of centuries ago—or earlier—have been making a comeback. New-fashioned haberdasheries (early 15th century) sell bespoke (mid-18th century) suits; trendy bars hire mixologists (mid-19th century). But no word from the distant past is as antique, or as popular in commerce in so many disparate ways, as apothecary.

My curiosity about apothecary was piqued last year when a new sausage-and-beer restaurant, Hog's Apothecary, opened in my hometown of Oakland, California. A curious name, I thought, for an establishment that sells food and drink rather than medicines, the traditional purview of apothecaries.

Then I began seeing 'apothecaries' everywhere. One, hewing close to the historical sense, was a compounding pharmacy, but several sold candles, or bath and beauty products. (In New York City, M.S. Apothecary uses the slogan 'Where Beauty Is a Drug.') Until it closed a few years ago, a San Francisco store called simply Apothecary sold children's clothing. An online home-décor retailer touts 'Apothecary Chic' (distressed-metal cabinets, glass jars with old-timey labels, wooden shelves). Evergreen Apothecary in Denver and The Apothecarium in San Francisco dispense medical marijuana. Chicago has Arch Apothecary, a 'luxury beauty and style bar' established in 2012, and it has Merz Apothecary, a pharmacy established in 1875. 'Because [Peter] Merz was of Swiss descent,' the website explains, 'he decided to call the store an ‘Apothecary' in the European tradition.'

How did one word 'in the European tradition' come to describe all these dissimilar businesses in the United States? For the answer, we need to time-travel.

'Apothecary' is a very old word indeed. It first appeared in English in the mid-1300s, imported from Old French, which had adapted a late-Latin word, apothecarius, meaning 'shop-keeper.' In English, too, apothecary originally meant a person: 'a shopkeeper, especially one who stores, compounds, and sells medicaments.' That sense is maintained by the Visual Thesaurus, which gives five synonyms for 'apothecary,' all describing professions: chemist, pill-pusher, druggist, pharmacist, and pill-roller. Toward the end of the 14th century, Geoffrey Chaucer mentioned an apothecary in 'The Nun's Priest's Tale': 'Though in this toun is noon apothecarie,/I shal myself to herbes techen yow.' In Romeo and Juliet, a 'caitiff wretch' of an apothecary sells Romeo the potion with which our hero commits suicide.

It wasn't only Shakespeare who held apothecaries in low regard. In his Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, first published in 1785, Francis Grose wrote that apothecaries were 'as superficial in their learning as they are pedantic in their language.' Grose documented several slang terms using apothecary, all of them disparaging: an apothecary's bill was a long bill; apothecary's Latin (also known as dog Latin) mangles the classical tongue; 'to talk like an apothecary' meant 'to prattle.'

But before Latin apothecarius there was a Greek source, apothēkē, which means 'a repository or storehouse'—a building, not a person. The Greek word and meaning gave rise to two linguistic cousins familiar to many of us today: French boutique (a small retail shop) and Spanish bodega (a small grocery store). It's this sense—apothecary as a place of business, not the person who runs it—that dominates today.

Until recently, apothecary had a musty reputation in American English. Its usage had declined steadily for the last 150 years (see the Google Ngram), and when it appeared at all, it was often in histories or in historical fiction such as The Apothecary's Daughter, a 2009 romance set in Regency England. Apothecary also shows up in the titles of how-to books about traditional remedies.

Then, over the last decade or so, apothecary began appearing in new contexts—like that Oakland gastropub I mentioned earlier. Oakland magazine explained the reasoning behind the Hog's Apothecary name: 'Just as a pharmacy serves an array of cures for ailments, so Hog's Apothecary serves a number of ‘cures' to its patrons.' Besides, the owner explained, sausage and bacon are 'cured' meats. It's a stretch, but it demonstrates the contemporary glamour of apothecary.

How did this medieval word become so chic in the 21st century? Nostalgia plays a role: a reaction to the disembodied virtual life, a yearning for experiences less mediated by technology and more informed by creativity and gentility. More specifically, I propose that the steampunk subculture, which blends elements of Victorian-era design with science-fiction and fantasy, is another important factor. Along with influencing fashion, invention, facial hair, and popular culture—the Doctor Who television series, the Robert Downey, Jr., Sherlock Holmes remakes—steampunk has inspired linguistic and artistic revivals. Ornate typography and illustration, as in the Hog's Apothecary logo, show the influence of steampunk.

For Americans, apothecary carries a whiff of the Old World, and especially Great Britain, which has been exerting a steady influence on the language of commerce. I'll explore this topic at greater length in a future column, but for now I'll just direct your attention to the aforementioned bespoke, which the Wall Street Journal traced to London tailor shops and found attached to an American investment firm, software company, and bicycle shop; and to stockist (a retailer or distributor), opening hours ('hours' in the U.S.), and queue(line)—all Britishisms used in the U.S. to add an imagined air of class and tradition to marketing copy.

Not for nothing, apothecary is fun to say.

In the eyes of the law, however, apothecaries are serious business. Here in California (and maybe elsewhere), the use of 'apothecary' is legally restricted to licensed pharmacies. The state board of pharmacy has, on at least a couple of occasions, wielded that law—enacted in 1905—against non-druggist apothecaries. In 2008, the board warned Apothecary, the San Francisco children's-clothing store, to either change its name or close its doors. 'Imagine ending up in legal hot water for not selling drugs,' a local newspaper wryly commented. The store owner chose to go out of business rather than rebrand.

So far, Hog's Apothecary and its kin appear to have escaped censure. Perhaps they've claimed the linguistic defense, citing the rich history of apothecary. The Greeks had a word for it, after all, and if apothēkē was their boutique or bodega, why can't it be ours?

A monastery's infirmary herb garden grew specialist plants that were used in medieval medicine to help the body heal itself. Here are nine plants that you'd find there which you can still grow in your own herb garden today.

Gardens dedicated to medicinal herbs alone were quite rare in medieval times, except in large institutions like monasteries, for example Rievaulx Abbey in Yorkshire (pictured), where there were lots of people to care for.

Medieval medicine was based on the notion of the body having four ‘humours' related to the four elements:

- blood (air) was hot and moist

- phlegm (water) was cold and moist

- yellow bile (fire) was hot and dry

- black bile (earth) was cold and dry.

It was the physician's job to work out how to restore the balance of a person's humours if they became ill, and so plants and herbs were ascribed properties to redress the balance. A cooling herb would be used if you were considered to have too much blood or yellow bile, for example.

Here are nine plants to sow for a herb garden inspired by monastic infirmary gardens in the Middle Ages:

(We wouldn't recommend brewing your own herbal remedies without plenty of research.)

Sage (Salvia officinalis)

Sage (Salvia officinalis) – by Isaac Wedin via Flickr/Creative Commons

Sage, whose first botanical name comes from the Latin salveo, meaning 'I am well' , was used by the Romans in medicine and cooking. As with some other herbs mentioned below, ‘officinalis' is a reminder of its monastic medicinal use — the officina being the monastic storeroom where herbs and medicines were stored.

In the medieval period sage was described as being ‘fresh and green to cleanse the body of venom and pestilence'. It was also chewed to whiten teeth and used very frequently in cooking along with lots of onions and garlic. This means that sage and onion stuffing has a medieval pedigree!

Sage is best grown in well drained soil with full sun and can be grown either from seed, from cuttings or from plug plants.

Medieval Apothecary Mask

Betony (Stachys officinalis)

Betony (Stachys officinalis) by Pryma – CC BY-SA 3.0

This was once an incredibly popular herb, and used for curing anything and everything you can think of – including a few extras like fear, ‘violent blood', and ‘chilly need'.

Depending on the variety, betony grows between 25cm and 90cm tall.

A monastery's infirmary herb garden grew specialist plants that were used in medieval medicine to help the body heal itself. Here are nine plants that you'd find there which you can still grow in your own herb garden today.

Gardens dedicated to medicinal herbs alone were quite rare in medieval times, except in large institutions like monasteries, for example Rievaulx Abbey in Yorkshire (pictured), where there were lots of people to care for.

Medieval medicine was based on the notion of the body having four ‘humours' related to the four elements:

- blood (air) was hot and moist

- phlegm (water) was cold and moist

- yellow bile (fire) was hot and dry

- black bile (earth) was cold and dry.

It was the physician's job to work out how to restore the balance of a person's humours if they became ill, and so plants and herbs were ascribed properties to redress the balance. A cooling herb would be used if you were considered to have too much blood or yellow bile, for example.

Here are nine plants to sow for a herb garden inspired by monastic infirmary gardens in the Middle Ages:

(We wouldn't recommend brewing your own herbal remedies without plenty of research.)

Sage (Salvia officinalis)

Sage (Salvia officinalis) – by Isaac Wedin via Flickr/Creative Commons

Sage, whose first botanical name comes from the Latin salveo, meaning 'I am well' , was used by the Romans in medicine and cooking. As with some other herbs mentioned below, ‘officinalis' is a reminder of its monastic medicinal use — the officina being the monastic storeroom where herbs and medicines were stored.

In the medieval period sage was described as being ‘fresh and green to cleanse the body of venom and pestilence'. It was also chewed to whiten teeth and used very frequently in cooking along with lots of onions and garlic. This means that sage and onion stuffing has a medieval pedigree!

Sage is best grown in well drained soil with full sun and can be grown either from seed, from cuttings or from plug plants.

Medieval Apothecary Mask

Betony (Stachys officinalis)

Betony (Stachys officinalis) by Pryma – CC BY-SA 3.0

This was once an incredibly popular herb, and used for curing anything and everything you can think of – including a few extras like fear, ‘violent blood', and ‘chilly need'.

Depending on the variety, betony grows between 25cm and 90cm tall.

Its flowers, generally purplish but sometimes white, appear between June and October. It's long-lived and slow-growing and prefers dampish but not waterlogged areas.

Medieval Apothecary Jars

Clary Sage (Salvia sclarea or wild clary is Salvia verbenaca)

Clary sage (Salvia sclarea) by H. Zell (Own work) CC BY-SA 3.0

Another member of the salvia family, Clary Sage was also known as ‘clear eye' and ‘Oculus Christi' (Eye of Christ) as its main use was as an eyewash, made by infusing sweet scented leaves in water.

It's a biennial with purple-blue flower spikes from late spring to mid-summer and attracts honey-bees and other pollinators.

Hyssop (Hysoppus officinalis)

Medieval Apothecary Building

Hyssop (Hysoppus officinalis) by Holger Casselmann (Own work) CC BY-SA 3.0

In medieval herb gardens, hyssop was considered a hot purgative. Drunk in oil, wine or syrup, it was meant to warm away cold catarrhs and chest phlegm. It was also rubbed on bruises to soothe them and had purifying, astringent and stimulant uses.

It has spikes of blue, pink, or red flowers and prefers well drained soil.

Rue (Ruta graveolens)

Rue (Ruta graveolens) David Midgley via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

This was used as a strong purgative for plague and poison, and as a holy water sprinkler in exorcisms. Its medicinal properties have now largely been disproved, and its use in cures may be dangerous. Its smell is a repellent to Japanese beetles, dogs and cats and it attracts some species of butterfly.

You can recognise rue plants by their bushy, bluish-green, fernlike leaves ,and yellow flowers with wavy edges and green hearts. Rue can grow up to 90cm tall.

Medieval Apothecary Names

Best grown in well drained soil with full sun – rarely needs watering. Take care when handling the plant – its sap can be a strong irritant.

Medieval Apothecary Tools

Chamomile or Camomile (Chamaemelum nobile)

Chamomile is said to revive the sickly and drooping plants growing near it. It's a very tough plant, sometimes grown in ‘chamomile lawns' — which take a lot of work to establish. Since the daisy-like flowers are very small, lots of them are needed to be of use.

Once you have enough of them, chamomile flowers are good for making sedative and digestive infusions that also combat flatulence. Chamomile tea with dittany, scabious and pennyroyal was a preferred medieval remedy against poison.

This perennial herb grows best in cool conditions and prefers part-shade and dry soil.

Dill (Anethum graveolens)

Dill (Anethum graveolens) by Carl Lewis via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

The word dill derives from the Anglo-Saxon dilla which means ‘to lull'. It was used as a kitchen herb for flavouring fish, pickles and pottages, as well as in the infirmary for cordials. Along with cumin and anise, its seeds were made into spice cakes to eat after rich meals or illness to help with digestion.

Its delicate fronds can reach 60-90cm in height.

Cumin (Cuminum cyminum)

Cumin (Cuminum cyminum) by Allium Herbal via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Infirmarers grew cumin to use its seeds in soothing ointments for the complexion and eyes, as well as for its culinary uses. Cumin was grown more widely than dill outside monastic gardens.

Peasant rents were sometimes paid in cumin, along with hens and eggs.

It's native to the Mediterranean and requires a long hot summer, so isn't the easiest plant to grow in the UK.

Comfrey – also known as Boneset (Symphytum officinale)

Medieval Apothecary Herbs

Comfrey (Symphytum officinale) by Matt Lavin via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Comfrey has a long history of use in medicine, and was grown in infirmary gardens for its power to heal wounds and inflammations and (as its nickname suggests) help to set broken bones.

Comfrey needs rich, moist, alkaline soil and generally prefers shady areas. It can grow up to 120cm tall and has long, hairy, deep-green leaves. Take care when handling the plant, which can irritate sensitive skins.

[ssba]